I received the following email:

Can you please recommend a few good books on heaven and hell? A friend is confused about why good people who do not believe Jesus is the only way don’t make it to heaven.

There are actually several different questions being asked here:

There are actually several different questions being asked here:

1) Is there a hell, and why do some people go there? (I’ve never heard anyone complain about the possibility of people “going to heaven.”)

2) Do “good people” who are not believing Christians all go to hell?

3) What about the “good Buddhist”? Is it fair for God to send good people who are not Christians through no fault of their own to hell? You do not actually mention this question, but it often lurks in the background.

I would answer briefly as follows:

The Good News

Christianity is not primarily about hell, but about God’s love for humanity despite the mess we have made of the world, and the way in which God has become a human being in Christ to “set things right” (N.T. Wright’s expression). The gospel (good news) is not “God is angry with you and wants to send you to hell,” but “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son. . .”

Why “Stuff Happens”

What’s wrong with the world? Is suffering, evil, and death on ontological problem (“just the way things are”) or a moral problem (the consequence of wrong human choices)? The Christian explanation for suffering, evil, and death is “sin.” It is not that “bad things happen to good people,” but that even so-called “good people” do bad things. A moral explanation for what’s wrong with the world is the only one that takes evil seriously or that offers any hope for a solution. If suffering, death, and evil are “just the way things are,” then there can be no ultimate solution.

The current culture supposedly does not believe in sin, but this is not really true. What has happened instead is that we have shifted from a “sin” culture to a “shame” culture. People do not want to believe in their own sin, but they have no problem in placing blame on other people, and “shaming them” when they cross some current cultural boundary. “Shaming” escalates, however, and simply leads to people “shouting each other down.” “Shaming” offers no room for forgiveness, change, or reconciliation.

Former TSM faculty member and my good friend Leander Harding says that “Sin is what other people do that I disapprove of. There are lots of things that I do that other people disapprove of, but I don’t call them sin.”

There are all kinds of signs in everyday culture that we are well aware of and believe in “other people’s” sins. We guard our email from spam and we filter our telephone calls because we are constantly on the alert for identity theft and online scams. People march in protest either for or against various causes, and current political divides indicate that both sides believe that those who disagree with them are not just mistaken, but immoral. Contrary to President Trump, we don’t believe “there are some very fine people on both sides.” Nor should we. White nationalists are evil. We live in a culture in which people constantly have to fear about the possibility that someone with a gun will take innocent lives. It is evil to shoot down innocent people in cold blood. There is a crisis about immigration in our culture, and people rightly believe that it is evil to separate small children from their parents and put them in cages. The “me too” movement has made it clear that sexual exploitation is evil, and our culture will no longer tolerate it. The fact that even those who are accused of racism quickly deny that they are racists makes clear that we agree as a culture that racism is evil.

Where the Christian doctrine of sin is helpful is that it reminds us that the problem is not just with those “other people,” but with us as well. If “all have sinned,” then all can be forgiven. If there is no sin, but only shame, then no one can ever be forgiven, and we all must live forever not only shaming others, but with the fear that others might shame us.

What “Salvation” Means

Crucial to the Christian claim is that in the incarnation, the cross, and the resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has taken on all of the suffering and evil in the world, and defeated it. As Dorothy L. Sayers wrote in her essay “The Greatest Drama Ever Staged,” on the cross, God has “taken his own medicine.” Because of Jesus, sin, death, and suffering will not have the last word.

A crucial point in the proclamation of the gospel is “God’s universal salvific will.” That is, everyone who has ever lived, came into existence because God loves them. God wills the salvation of everyone, even the worst sinner; Jesus Christ has died for everyone, and God has done and will do everything in his power to bring about the salvation of every single individual. A Collect from the Book of Common Prayer, begins: “O God, you declare your almighty power chiefly in showing mercy and pity . . .” In the words of Prosper of Aquitaine, “If anyone is saved, it is because of the goodness of God; if anyone is lost, it is their own fault.”

This has implications for theological anthropology, or our understanding of what it means to be human. The following can be said of every person who has ever lived: “You are created in the image of God, you are a sinner who has been redeemed by Jesus Christ, and God truly wills your salvation.”

(A strict Calvinist would not agree with the above. That’s one of the reasons that I am not a Calvinist.)

It is important to keep in mind that salvation (“heaven”) is not “Disneyland,” a place where everyone goes to “have a good time.” Rather, salvation is redemption – the re-creation and restoration of the entire universe to be the way in which God intended it to be. Salvation is not just “living forever,” but reconciliation with and living with, knowing and loving the God who is our Creator. 1 Cor. 13:2 states that we shall “see [God] face to face,” and know as we are known. 1 John 3:2 states: “[W]e know that when he appears, we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is.” In the words of the famous prayer from Augustine’s Confessions, “You have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.”

To be created in the image of God means that we are created for fellowship and union with God, that God has created the world to share his love and goodness with creatures. We do not exist to “do our own thing,” but to know and love God, as God knows and loves us. We are created to be loved by God and to love him in return.

To be “sinful” means not just that “everyone does bad things,” but that we have turned our backs on our Creator, and thus missed the whole point of our existence. As Jesus summed up the two great commandments, the first commandment is to love God with all of our hearts, souls, and minds, and the second is to love our neighbors as ourselves. Sin is not just “doing bad things,” but failing to love as we have been loved. In the words of the “General Confession” from The Book of Common Prayer, “We have not loved you with our whole heart, we have not loved our neighbors as ourselves.”

Moreover, and most important, salvation or redemption is about reconciliation to God and neighbor. It is about being restored to the love for which we were created. Salvation is about forgiveness of sins, but also about union with Jesus Christ – the risen Christ sharing his life with us – knowing and loving Christ, becoming “friends” with him (John 15:15), and being in communion with him and his body, the church. Salvation is not merely about individuals “going to heaven,” but about becoming members of the church, the people of God, the body of which Jesus Christ is the head, the community of people who are learning to love God with all of their hearts and their neighbors as themselves.

Hell, no? or The Hell there is!

But if eternal life (salvation, redemption, “heaven”) means life forever with God, loving him and knowing him as he is for who he is, being part of the body of Christ, loving and forgiving our neighbor whom we now love as ourselves, what then of those who want nothing to do with God or Christ? What then of those who do not want to forgive their neighbor, or to love him or her as themselves?

The doctrine of hell is not at the heart of Christianity, but I would suggest that it is the “flip side” of the gospel – the good news that God wants to reconcile us to himself so that he can share his life with us, that salvation is about union with and sharing in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, of being part of this new community the church, who live to love God with all of their hearts and their neighbors as themselves. “Hell” is the doctrine that says that although God truly loves and wills the salvation of everyone he has ever created, that Jesus Christ has truly died for everyone, and sincerely invites everyone who has ever lived to share in this new life in Christ, and to become part of this new community of love and forgiveness, no one will be forced to do so. “Hell” means that, despite all God has done for their salvation, those who refuse to be reconciled with God and one another, will be allowed to do so forever. As C.S. Lewis wrote in The Problem of Pain, “the doors of hell are locked on the inside.”

There are several possible theological positions that have been taken in response to the doctrine of hell, and a number of questions that need to be addressed.

“Pluralism” is the position that says that “all roads lead to the same destination.” Everyone will be saved by whatever religion or belief they follow. This is the position associated with liberal Protestant theologian John Hick. Former Episcopal Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori infamously stated that Jesus was “the way” of salvation for Christians, but that other people had their own ways. The problem with “pluralism” is that it ultimately does not take any one religion seriously, and it reduces Jesus to a good example or a wise teacher rather than the Savior of the world. Pluralism claims to respect every religion, but it does not respect any of them seriously enough to actually consider their fundamental claims, and it does not take seriously the central claim of Christianity that Jesus Christ is the Savior of the world.

“Universalism” is the position that eventually everyone will be saved. Many theologians who have been orthodox in every other respect seem nonetheless to have been universalists, including theologians from whom I have learned a lot. Reformed theologian Karl Barth, Roman Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, the Scottish writer George MacDonald (who influenced C.S. Lewis), Anglican F. D. Maurice, Eastern Orthodox writer David Bentley Hart, all seem to have been universalists. The main problem with universalism as I see it, is that it seems to conflict with the plain teaching of the New Testament, including especially the teaching of Jesus, e.g., the parables of the sheep and the goats, or the rich man and Lazarus. It also ignores the problem of those who “just say no.” Assuming that God has done everything possible for our salvation, is it not possible that some people might refuse that gift forever?

If we reject both pluralism and universalism, there seem to be two (or possibly three) final possible positions.

Exclusivism is the position at the opposite extreme from both pluralism and universalism. Exclusivism is the position that only those who have explicit faith in Jesus Christ will be saved. In other words, everyone is lost except for those who have consciously exercised faith in Jesus Christ. This has certainly been the position of many orthodox Christians. The problem with exclusivism is that it seems to fly in the face of the universal salvific will of God. If only those who are saved who explicitly have faith in Jesus Christ, then it would seem that the majority of the human race will not be saved. This would seem to imply that God’s will that no one should perish, but that all will reach repentance (2 Peter 3:9) would largely be defeated.

“Inclusivism” is the position that Jesus Christ saves, and that ultimately anyone who is saved will be saved because of the person and work of Christ. However, we cannot presume that only those who have exercised conscious and explicit faith in Christ before their death will be saved by Christ. If we take seriously that God wills everyone to be saved, and that Jesus Christ has died for everyone, that God’s grace is active everywhere, then surely it is possible that God can save even those who do not yet know that Jesus Christ is their Savior. This does not imply that everyone is saved (universalism), or that every path leads to salvation (pluralism). It does imply that God can work in mysterious ways in those who do not (yet) have explicit faith in Christ, and if (and when) they are saved, it will be Christ who saves them. If the “good Buddhist” is ultimately saved, he or she will not be saved by being a “good Buddhist,” but because Jesus Christ has died for her sins, and because ultimately (whether in this life or the next), she will come to know Jesus Christ as her Savior. (This is a position that has been held by Roman Catholic theologians such as Karl Rahner, by C.S. Lewis, and by many contemporary Christian theologians.)

Missiologist Leslie Newbigin, and former Dean and President of Wycliffe College George Sumner, have advocated a position identified as “particularism.” Newbigin has complained that “inclusivism” focuses too much on the salvific fate of the individual, and does not take seriously enough the way that religious life takes place within particular communities. The biblical story is not concerned with individuals going to heaven and hell, but with the redemption and eschatology of the entire cosmos – a new heaven and a new earth. God brings salvation through communities; Israel is God’s people elect as the representative of the nations. The incarnate Jesus Christ is elect as the one who bears the sins of the entire world. Jesus’ followers live in the midst of the fallen world as signs of God’s kingdom, not as the select saved in the midst of the many lost, but as the sign of God’s intent to save all human beings. There will indeed be a final judgment, but there will also be surprises. Some who think they will be saved will not be, and vice versa.

George Sumner complains that Rahner’s version of inclusivism tends to reduce grace to psychology, and loses track of what Sumner calls “Christological final primacy.” “Final primacy” is the position that all other truths must be brought into relation to the single norming truth of Jesus Christ, who is the First Truth. Christ is the “First Truth,” the “unknown God” of Acts 17, the “Word who enlightens everyone coming into the world” (John 1:9), the One through whom even pagans have knowledge of the law “written on their hearts” (Rom. 2:15).

According to Sumner, the non-Christian religions contain “partial truths,” but they also contain falsehood and ignorance. What is of chief importance is to remember that the goal (telos) of the narrative of salvation is Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ must be at the center of any theological affirmation of salvation. To abandon Christological final primacy is to abandon Christian faith.

I would suggest that Newbigin’s and Sumner’s “particularism” and “final primacy” are not rejections of “Inclusivism” so much as warnings against the dangers of “Inclusivism” turning into “Pluralism.” Newbigin and Sumner agree with “Inclusivists” that salvation is possible for those who do not have explicit Christian faith in this life, but they also want to be emphatic that this salvation comes from Jesus Christ, not from being a “good Buddhist.”

Another possible way of expressing “inclusivism” would be to reverse the original premise of exclusivism. Exclusivism states: “No one is saved except for those who have explicit faith in Jesus Christ.” Inclusivism would state rather: “Everyone is saved except for those who finally refuse to receive forgiveness, grace, and reconciliation in Jesus Christ.” Inclusivism is the position that if the door to redemption is finally shut, it will only be shut by those who refuse to the end to receive God’s redeeming and reconciling grace in Jesus Christ, and that the door to hell in the end will be shut from the inside. God has done, and will do everything he can, either in this world or the next, to save all who will be saved, and no one will be lost because they did not receive the possibility of salvation.

There is one final position I should mention: “Conditional immortality” or “annihilationism.” This is the position that identifies hell not as a continuing eternal conscious state of separation from God, but as the ceasing to exist of the lost. Unlike the saved, who live in God’s presence for eternity, the “damned” simply are no more. This is a position that has been held (even if tentatively) even by some traditional Evangelical theologians such as John Stott. Whatever one thinks of “annihilationism,” it would be a rejection of both pluralism and universalism, and it would be a variation on traditional understandings. Annihilationists would presumably be either exclusivists or inclusivists. (The theological critique of annihilation would be the same as that of universalism. It seems to be in conflict with the teaching of Scripture.)

Some final reflections:

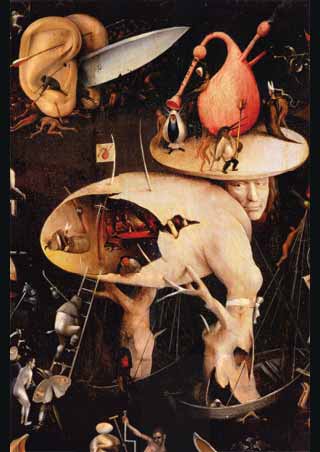

What about the symbolism of hell? I think it important to recognize that the language of hellfire and brimstone connected with hell is metaphorical and symbolic. The point of the imagery is not to give a literal description of hell anymore than the symbolism of a city made of gold and precious stones is a literal description of the New Jerusalem (Rev. 21), but to emphasize the great tragedy of losing out on salvation. Ultimately, hell is the prospect of eternal separation from God. Some Eastern Orthodox theologians have even suggested that hell is the burning love of God as experienced by those who eternally reject that love. In Dante’s Inferno, he uses many different images for hell, including that of a frozen lake at the deepest level of hell. In C.S. Lewis’s book The Great Divorce, he imagines hell as a kind of “gray city.” The great loss of hell is not physical pain, but the missing out on the possibility of sharing in the Divine Love for which we have been created. Returning again to Augustine’s Confessions, “You have made us for Yourself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in You.” To forever have that thirst for God who can alone makes us happy and who can alone give us rest, and yet, because we have decided forever to prefer our own wills to the joy offered us by our Creator, to be eternally restless and eternally unsatisfied, would indeed be hell.

Finally, the most important thing to remember about the Bible’s imagery of hell is that it is always addressed personally and existentially, and calls for a personal response. The Bible does not speak of hell in order for us to speculate about or to imagine the fate of others, but always as a personal reminder: Am I myself in danger of rejecting God’s promise of grace and forgiveness? Is there a danger that I myself might turn my back on God’s love? Am I myself in danger of missing the very purpose for which God created me?

Bibliography

C.S. Lewis has perhaps written more thoughtfully on hell than any other modern writer:

The Problem of Pain. Macmillan, 1952.

Lewis has a chapter on “Hell,” in which he addresses some of the main objections people have raised to the doctrine of hell.

The Great Divorce. Macmillan, 1946.

C.S. Lewis’s imaginary story of a bus ride from hell to heaven in which hell’s residents are given a second chance.

N. T. Wright

Simply Good News: Why the Gospel is News and What Makes it Good. HarperOne, 2017.

This is a good starting point to get to the heart of what Christianity is about. Christianity is about the “Good News” that God is “setting things right.” Christianity is not primarily about “going to heaven or hell.”

Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, Resurrection and the Mission of the Church. HarperOne, 2008.

Wright corrects a lot of common misconceptions about “heaven.” He has a short discussion of “hell.”

Leslie Newbigin, “The Christian Faith and the World Religions,” Keeping the Faith: Essays to Mark the Centenary of Lux Mundi, Geoffrey Wainwright, ed. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1988.

This is Newbigin’s critique of Pluralism and Inclusivism in favor of “Particularism.”

George Sumner. The First and the Last: The Claim of Jesus Christ and the Claims of Other Religious Traditions. Eerdmans, 2004.

This is one of the best discussions of the implications that Jesus Christ is the universal Savior (what he calls “Final Primacy”) has for other religions.

Neal Punt. Unconditional Good News: Toward an Understanding of Biblical Universalism. Eerdmans, 1980.

This now older book challenges the central premise of exclusivism by suggesting as an alternative to “Everyone is lost except for those who have faith in Jesus Christ” that “Everyone is saved except for those who finally refuse God’s grace in Jesus Christ.”

Jerry Walls. Hell, The Logic of Damnation. University of Notre Dame Press, 1992.

Heaven, The Logic of Eternal Joy. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Purgatory, The Logic of Total Transformation. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory: Rethinking the Things That Matter Most. Brazos, 2015.

Jerry Walls is an important Evangelical Methodist philosopher who addresses some of the traditional objections to the doctrines of heaven, hell and purgatory(!) in these books.

“Some Eastern Orthodox theologians have even suggested that hell is the burning love of God as experienced by those who eternally reject that love.”

This is something I’ve wondered about even before I knew about the Orthodox connection. Could it be that everyone ends up in the same place, but those who are not in Christ experience his presence as a burning fire? Could what the redeemed find the true source of their longings be unbearable to the lost? Of course, this is just speculation on my part, and I certainly would not defend it as a settled dogma.

Comment by David — July 18, 2018 @ 6:09 am

Bill, I know you’re not a Calvinist, and you make an eloquent defence of the universal divine offer of grace. But I’d be interested in what you think of the logic of Pascal’s argument in the second Provincial Letter.

Comment by David — July 18, 2018 @ 6:17 am

On the question of annihilationism you write that ‘This is a position that has been embraced even by some traditional Evangelical theologians such as John Stott.’ This is a common mistake. John Stott suggested that the impenitent will finally be destroyed, claiming to hold his position “tentatively.” It is important to be fair to Dr. Stott and not call this an “embrace”–he knew enough about Christian history to know his position was not the historic Christian one [David L. Edwards and John Stott, Essentials (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1988), pp. 313-320].

Comment by Kendall harmon — July 18, 2018 @ 4:30 pm

Thanks, Kendall. Correction made.

Comment by William Witt — July 18, 2018 @ 6:42 pm

David,

I think that this would likely be the implication of the theory that hell is God’s love as experienced by those who reject it.

My concern is that the picture of the “same place” is perhaps too “individualist,” missing out on the corporate dimension of salvation. N.T. Wright keeps playing the same tune over and over — that Christian eschatology is not about “going to heaven,” but about re-creation, a new heaven and a new earth, and that there is a communitarian dimension to this. It strikes me as odd that the “New Earth” would be populated simultaneously by some groups of people who were enjoying God’s presence, but also by others who hated it. That feels a bit too much like the way things are now. But perhaps I’m being overly literalist.

Comment by William Witt — July 18, 2018 @ 6:49 pm

Thanks for the thoughtful post, Bill. I think that the distinction between sin and shame is helpful — but I wonder if the current culture’s preoccupation with the latter in fact provides a gospel opportunity? It seems to me that in evangelism that convincing people that 1) sin exists and 2) they sin puts a lot of heavy-work up front. Perhaps we should be leading with the good news that Jesus’s reconciling work also deals with the problem of our shame. (This is not to discount the reality of sin! Simply wondering if re-ordering our approach to deal more directly with this cultural phenomenon would be of use.)

Comment by Christine P — July 18, 2018 @ 10:20 pm

David,

Pascal’s logic brings up a reasonable criticism of the “Dominican” interpreters of Aquinas of his time (actually followers of Domingo Báñez) that an intrinsic difference between sufficient and efficacious grace is logically incoherent. If no one is saved by “sufficient” grace, if “efficacious” grace is necessary for salvation and given only to the elect, then “sufficient” grace is not really sufficient. As you know, I wrote my dissertation on Arminius and raised a similar criticism against Báñezianism.

At the same time, neither the “Jesuit” position (Molinism) nor the Báñezian position are really accurate representations of Aquinas’s own position. Part of the problem is that Aquinas used terminology (such as the distinction between “operant” and “cooperating” grace) without addressing the specific questions that were later debated at the time of the Reformation, such as whether there is an inherent distinction between sufficient and efficacious grace or whether efficacious grace is simply sufficient grace that has been actualized through faith. Depending on which passages of Thomas are emphasized, Thomas can be read as supporting either “Thomism” or “Molinism.”

More careful studies in the twentieth century have led to better readings of Thomas. The two most significant interpretations are probably Bernard Lonergan’s Grace and Freedom: Operative Grace in the Thought of St.Thomas Aquinas and Henri DeLubac’s The Mystery of the Supernatural and Augustinianism and Modern Theology. Certainly De Lubac and the Nouvelle Théologie movement have been the most stimulating for modern discussions of grace, and have proven influential beyond the circles of Roman Catholicism.

Rather than focusing on distinctions between sufficient and efficacious grace, De Lubac focused instead on showing that the late Medieval notion of “pure nature” is foreign to Aquinas’s thought. For Thomas, every human being is created in the image of God with an orientation toward the beatific vision, and this does not disappear with the fall. (There is no such thing as “pure nature.”) This has important implications for a doctrine of universal salvific will, since every human being is oriented toward union with God.

I also think that a more sophisticated notion of “dual causality” is more helpful to a discussion of grace than the Dominican/Molinist debate about the distinction between sufficient and efficacious grace. Both Dominicans and Molinists seemed to operate with the assumption that human and divine causality were operating on the same level of reality, so that “grace” and “free will” become a “zero sum” game. For Dominicans, unless there is an intrinsic distinction between sufficient and efficacious grace, human beings “save themselves” by exercising faith through their own free wills. For Molinists, if there is such a distinction, then free will disappears as “efficacious” grace leads to determinism. (Note that Pascall does not hesitate to use “determinist” language.)

I have been influenced in my understanding of “dual causality” largely by Anglican Austin Farrer, and to a lesser extent by George Hunsinger’s discussion of Karl Barth. I have some discussion here:

https://willgwitt.org/theology/austin-farrer-anglican-philosophical-theologian/

https://willgwitt.org/theology/notes-on-predestination/

Comment by William Witt — July 18, 2018 @ 10:48 pm

Christine,

Good point about “shame” as a gospel opportunity. In a discussion about the distinction between “Law” and “Gospel,” Lutheran theologian Philip Melanchthon emphasized that unless God was seen as a “lovable object,” he could not trusted but only feared. Until people can hear the good news of the Gospel, the “law” is perceived as a threat and God (as law-giver) is avoided. “Sin” talk is perhaps the contemporary equivalent of “law” — so loaded with negative connotations of arbitrary condemnation that the mere word can shut down conversation. I intentionally used the notion of “shame” as a way of making a connection that I hoped might get past that initial reluctance — but a lot more could certainly be done.

Comment by William Witt — July 18, 2018 @ 11:05 pm

Thanks, Bill, for your responses.

Comment by David — July 19, 2018 @ 4:04 pm

Bill,

“…strict Calvinist…” There is some good work being done right now on John Davenant and hypothetical universalism in the Reformed Tradition, the most interesting point being that Dort allows (even if it really doesn’t like it that much) hypothetical universalism (Davenant arguing for as much as part of the English delgation at the Synod).

Ryan

Comment by Ryan Clevenger — September 22, 2018 @ 1:45 pm