Ephesians 4:1-16

John 17:11-26

The epistle reading from Ephesians and the reading from John’s gospel are perhaps the two single most frequently cited biblical passages about the unity of the church. Certainly unity is a central theme in both passages: Ephesians 4 rings the changes one the word “one”: There is one body, one Spirit, one hope, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all (Eph. 4:4-6). John has what is sometimes called Jesus’ High Priestly Prayer, where he prays that his followers will be one even as he and the Father are one (John 17:11,22). And, of course, unity is one of the four classic marks of the church: The church is one, holy, catholic, and apostolic.

The epistle reading from Ephesians and the reading from John’s gospel are perhaps the two single most frequently cited biblical passages about the unity of the church. Certainly unity is a central theme in both passages: Ephesians 4 rings the changes one the word “one”: There is one body, one Spirit, one hope, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all (Eph. 4:4-6). John has what is sometimes called Jesus’ High Priestly Prayer, where he prays that his followers will be one even as he and the Father are one (John 17:11,22). And, of course, unity is one of the four classic marks of the church: The church is one, holy, catholic, and apostolic.

What is the nature of the church’s unity that is such a major theme in these passages? There have been numerous answers to this question given in the history of theology. The 39 Articles and the Lutheran confessions speak of that unity in terms of activities that the church performs: The church is where the word is rightly preached and the sacraments rightly administered. The Roman Catholic Church has historically placed that unity institutionally: The church consists of all those who are in communion with the pope, the bishop of Rome. Anglo-Catholics have focused on historical continuity. The church is rightly found in those churches who can trace their succession through a series of bishops to the apostles. In the last century or so, many of the Orthodox have focused on Sobornost, a notion of the church as a community or fellowship based in freedom and love. In the last several decades, Christian ethicists such as Stanley Hauerwas have focused on the understanding of the church as a community of character, of Christian discipleship as a path of virtue whose primary focus is following the way of Jesus in the non-violent way of the cross.

What all of these descriptions have in common is that they are descriptions of the church from our point of view, from the ground up, as it were. Sometimes it helps to look at things from a different point of view. What is different about the way in which Ephesians and the Gospel of John look at the unity of the church is that they look at things from the opposite point of view, not from the ground up, but from the top down, from a God’s-eye point of view, as it were.

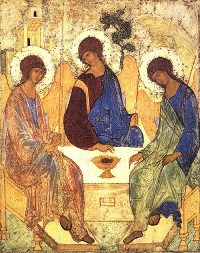

Both Ephesians and the Gospel of John point to the unity of the church first in the unity of the Trinitarian persons. The church is one because God is one. But God is not simply one as a monad. God is a unity of love between the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. In Ephesians, Paul writes: “There is one body and one Spirit . . . one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all” (Eph. 4:4-6). John records Jesus’ prayer “that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us . . .” (John 17:21). We might read John’s approach as binitarian rather than trinitarian, except that in Jesus’ Last Supper discourse in John, he had already talked at great length about the Comforter, the paraklete, whom Jesus says, he will “send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father.” (John 15:26). So the church’s unity originates first in the unity of the Trinitarian persons. Again, the church is one because the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are one.

Second, the church shares in the unity of the Trinitarian persons through the person, the work, and the presence of the incarnate, crucified and risen Jesus Christ. It is because the church is one with the risen Christ that we can be one with the Trinitarian persons. The church is Christ’s body as it dwells in Christ and shares in the love between the Father and the Son and is indwelt by the Holy Spirit. Paul writes: “Speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and held together by every joint with which it is equipped, when each part is working properly, makes the body grow so that it builds itself up in love.” (Eph. 4:15-16). In John’s gospel, Jesus prays: “The glory that you have given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one. I in them and you in me, that they also may be in us . . .” (John 17:22). And earlier, in John chapter 15, Jesus had said: “I am the vine; you are the branches. Whoever abides in me and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from me you can do nothing” (John 15: 5).

Third, this union between Christ and the church that, in turn, leads to a union with the Trinitarian persons, has a moral dimension. A real moral transformation and change takes place as the church that is united to Christ comes to be like Christ. So Paul writes, “I . . . urge you to walk in a manner worthy of the calling to which you have been called, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph. 4:1-3). Humility, gentleness, patience, love, peace: this is virtue language, and Paul says that these are the kinds of virtues that follow necessarily from what he calls the “unity of the Spirit.” In John, Jesus prays: “Sanctify them in the truth” (John 17:17). Again, earlier in John, Jesus had said: “If you love me, you will keep my commandments” (John 14:15) and “Whoever abides in me . . . will bear much fruit” (John 15:5). Union with Christ and with the Trinity means that the church will live as Jesus lived.

Fourth, there are two primary ways in which both Ephesians and John speak of this fruit of union with Christ being manifested in the lives of Christians in the church: Truth and love. And both are equally important. Paul brings both of them together: “Speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ” (Eph. 4:15). In John, Jesus prays “Sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth” (John 17:17). Earlier in the chapter Jesus had prayed: “This is eternal life, that they know you the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent” (v. 3). At the end of the prayer, Jesus draws the connection between knowing this true God and love: “I made known to them your name, and I will continue to make it known, that the love with which you have loved me may be in them, and I in them” (v. 26).

In contemporary culture, people talk about truth and love as if they are mutually incompatible. Those who claim to be concerned about truth are criticized for being arrogant or intolerant. Love, on the other hand, is identified with tolerance, inclusiveness, and pluralism, which, by definition, means to embrace pluriform or multiple versions of the truth. On the other hand, those who claim to know the truth only too often live up to the stereotype of being arrogant and intolerant, and accuse those who talk about love of being relativists. Within the church, predictable divisions line up between so-called progressive or liberal Christians who claim to follow Jesus’s example to “love your neighbor” (Mark 12:31) and not to judge (Matt. 7:1), and so-called conservative Christians who demonstrate their concern for theological orthodoxy by turning not only on liberals but all to often on one another.

However, in the Bible, truth and love are intimately connected because both are rooted in the nature of the one true God who so loved the world that he gave his only Son (John 3:16). The same Jesus who proclaims in John’s gospel, “You will know the truth and the truth shall set you free” (John 8:32) also says to his disciples “As the Father has loved me, so have I loved you. Abide in my love” (John 15:9). The same apostle who writes of “speaking the truth in love” in our epistle reading also prays a prayer that brings together the Trinitarian relation between truth and love: “I bow my knees before the Father from whom every family in earth and heaven is named . . . that he may grant you to be strengthened with power through the Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith – that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have the strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fullness of God” (Eph. 3:14-18). That prayer is a rather concise definition of the unity of the church.

There is also a sacramental, and even an institutional dimension to the church’s unity. Paul specifically connects the trinitarian unity of the church to the sacrament of baptism: “There is one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Eph. 4:5). Paul also writes: “he gave the apostles, the prophets, the evangelists, the shepherds and teachers to equip the saints for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ”(Eph. 4:12). In Jesus’ High Priestly Prayer, he speaks of the distinctive role that has been given to the apostles and their successors: “As you sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world” (John 17:18). Jesus also prays, “I do not ask for these only, bu also for those who will believe in me through their word” (v. 20). If all that talk about truth and love speaks to the Evangelical dimension of the church, then truth and love are embodied concretely in the church in its catholic dimensions. There is no church without sacraments and gathered worship. There is no church without an ordered ministry that continues the task of the apostles.

And, finally, the unity of the church has a missional purpose. The church is distinct from the world, and yet has a mission to the world. In the concluding words of Jesus’ prayer, he states the purpose of the church’s unity. On the one hand, the church is distinct from those who are not the church. Jesus says: “I have given them your word, and the world has hated them because they are not of the world, just as I am of the world” (John 17:14). At the same time, Jesus also prays that the church may be one for the sake of the world: “that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that you sent me and loved them even as you loved me” (v. 23). The church’s call is to let the world know of the love with which the Father and the Son love each other, the love that dwells in the church because the church is one with Christ, and the church is the body of Christ, the body whose head is Christ, the body that grows so that “it builds itself up in love” (Eph. 4:16). And the world will not know of this love if the church is not one, and if the members of the church do not love one another.

That is a very brief outline of the theology of the church that we find in the readings in Ephesians and John’s gospel. This outline has a lot in common with the different understandings of the church that I mentioned earlier. A church whose unity is grounded in the truth and love of the Trinity will be a church where the word is rightly preached and the sacraments rightly administered. A church whose unity is grounded in the truth and love of the Trinity will be a church with historical continuity with the apostolic church, and an institutional unity: sacraments and church orders are important. A church whose unity is grounded in the truth and love of the Trinity will be a church of Sobornost, a community or fellowship based in truth and love. And, finally, a church whose unity is grounded in the truth and love of the Trinity will be a a community of character, a band of Christian disciples who practice the virtue of following the way of Jesus in the non-violent path of the cross.

However, this also leaves us with a problem. The church is not one. All of us who are members of modern Christian churches belong to churches that are, in some sense, broken. The Eastern and Western churches have not been one for a thousand years. All of us who are Western Christians have lived with our own divisions for half a millennium. But even the Eastern churches have their divisions. Ambridge, Pennsylvania, probably has more iconostases per capita than any town in North America. When my wife Jennie and I first moved here we went on the Ambridge church tour in which we visited the Byzantine Catholic, the Ukranian Catholic, the Russian Orthodox, and the Coptic churches in Ambridge. The priests of these various churches each reminded us of how their church was the one true church founded by Christ. However, our favorite was the guide at the Coptic Church who simply said: “We’re an ancient Catholic church. We’ve had some important members, like St. Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria.” If the church’s unity speaks to the world of the love the Triune God, then what message does our disunity speak?

I cannot come up with a definitive solution to this problem of disunity in the last few minutes of this homily. I would make two suggestions, however. First, I don’t think we do much to help the problem of disunity when we view the problem of the division of the church as someone else’s problem. It is easy to think that the problem of church unity would be solved if everyone in all those other churches would just come around to realizing that my church is right and their church is wrong. And, of course, if they think the same thing about me we’re back where we started from. The irony is that this attitude reflects a lack of the very kind of love that Jesus claims is the essential sign of the unity of the church. If I simply assume that the church’s lack of unity is the other guy’s fault, then I have missed the point of the church’s unity.

Second, while I think that moves toward institutional unity and ecumenism are good things, I think that there is a fundamental task that all Christians need to undertake right where they are, while we are waiting for ecumenical commissions and dialogue groups to cross their t’s and dot their i’s. Ephesians and John tell us that the unity of the church starts from the top down, from the unity of the Trinity. The church is composed of those people who are one with one another because they are first one with the Triune God, because they dwell in Christ, and Christ’s Spirit dwells in them. It is through that indwelling that truth and love come to fruition. As Paul writes, “speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ . . . when each part is working properly,” the “body [will] grow so that it builds itself up in love” (Eph. 4:15-16). What that means practically is that there will be no church unity unless we first love Jesus, and unless we also love our brothers and sisters in Christ, right where we are, certainly beginning with those Christians who are in our own churches – and sometimes they are the hardest to love – but also going out of our way to get to know and love those of our brothers and sisters in Christ from whom we are now divided. That in itself is a tall order, and it is a good place to start.