Feast Day of St. John the Baptist

Isaiah 40: 1-11

Acts 13:14b-26

Luke 1:57-80

In what follows, I am going to depart from the usual way in which responsible expository preachers are supposed to preach sermons. I am not going to focus primarily on the meaning of the biblical texts themselves. Rather, I am going to look at the slightly different question of how it is that we as Christians make sense of the texts, how it is that the church has read these particular texts, and particularly the text in Isaiah. Because, frankly, there is a bit of a problem.

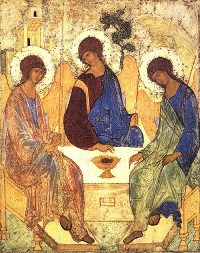

Let me explain what I mean by referring to an icon called The Hospitality of Abraham, that shows three angels sitting around a table. (For backround, see Solrunn Ness, The Mystical Language of Icons, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), pp.36-37) It is based on the story from Genesis 18 in which three men appear to Abraham, and Abraham offers the men hospitality. There are some odd details about the story. The narrative begins by stating that The LORD appeared to Abraham by the oaks of Mamre, and throughout the narrative Abraham speaks to one of the visitors, who promises Abraham that he will have a son, and later he and Abraham have a long discussion about whether or not Sodom is going to be destroyed. Throughout the narrative, this visitor who speaks with Abraham is referred to as the LORD.

The icon has a second name. It is also called “The Old Testament Trinity,” and the Eastern Church in particular has identified these three visitors with the divine Trinity. John of Damascus says: “Abraham did not see the divine nature, for no one has ever seen God, but he saw an image of God and fell down and worshiped.” (See John of Damascus, On Holy Images, part 3, ch. 4.) In the icon, the figure on the left is identified with the Father; the figure on the middle is identified with the pre-existent Word or Logos. The one on the right is identified with the Holy Spirit.

The historical background to this interpretation of the Genesis story has rather interesting, if problematic, roots. The Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria noted that in the narrative Abraham addresses the three men (plural) in the singular as LORD. Philo suggested that this indicates that there was some kind of triad in God, and, since the Pygathorean philosophers believed that three was the perfect number, finding this number three in an appearance of God to Abraham demonstrates that God is perfect. While Christians did not follow Philo in his Pythagorean speculation, they were more than willing to follow his interpretive method by suggesting that the passage showed that, even in the OT, God is revealed as Trinity. (See Gerald Bray, “Allegory,” Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible, Kevin J. Vanhoozer et al, eds. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005), 34-36)

We know this way of interpreting the Bible as “allegorical” or “figurative’ interpretation. “Figurative” interpretation is a way of reading the text in other than its literal sense to suggest that there is some other equally fundamental meaning, maybe even more fundamental than the original one. This side of the Reformation and the Enlightenment, we tend to look down on it. A first rule of modern biblical interpretation is that the text has to be interpreted in its literal historical sense. Heirs of the Reformation are sometimes willing to distinguish between typology and allegory, but generally figurative reading is bad. Clearly there is something odd going on in the Abraham story, but the original author of this passage in Genesis was not thinking about the later doctrine of the Trinity. In the discussion of this passage in the The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, prepared by Roman Catholic scholars, one would never know when one reads their exegesis of this passage, that anyone had ever thought it had anything to do with the Trinity. Modern biblical scholars, even Roman Catholics, ones have learned that lesson. (One of the chief complaints of the Protestant Reformers at the time of the Reformation, was that Roman Catholic biblical interpretation depended on allegory.)

That leads us to this morning’s Isaiah reading. If one reads modern commentaries on Isaiah, one finds that this passage marks the beginning of a major division in the book of Isaiah, marking chapters 40-66, usually referred to as Deutero-Isaiah. The setting of the book is after the exile of Israel to Babylon, and the prophet is announcing that the remnant of those Israelites who have been in captivity, are finally going to be freed, and are going to return to their ancestral homeland. That is how the scholars interpret the text. It is what is called its literal historical sense.

However, if we look at the Christian tradition of interpretation of this text, we find, as John Cleese used to say on the British television comedy Monty Python, “something completely different.” Handel’s Messiah begins with this reading: “Comfort, Comfort Ye my People,” (Is. 40:1) and then goes on to “And Every Valley Shall Be Exalted” (Is. 40:4) followed by “And the Glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.” (Is. 40:5) Handel has one Old Testament reading after another after another that all lead in a particular direction: “For unto us a child is born, unto us, a son is given.” (Is. 9:6) Handel thinks the readings are about Christmas. Without warning, he suddenly shifts from Old Testament readings to passages from Luke about shepherds watching their flocks in the field by night (Luke 2:8). And then, again without warning, he goes back to the Old Testament. And the rest of The Messiah is a hodge podge of shifting back and forth between Old Testament and New Testament readings. Even after the resounding “Hallelujah Chorus,” reciting the Book of Revelation (Rev. 19:6), Handel bounces back to Job, “I know that my Redeemer Liveth” (Job 19:25). Can you imagine what it would be like to take a certain kind of modern biblical critic to a performance of Handel’s Messiah?

This morning’s biblical readings are the readings for the feast day of John the Baptist. And the Old Testament reading is Handel’s opening passage from Isaiah. And we know why. All four gospels identify John the Baptist with this passage from Isaiah 40. Mark’s gospel begins with, “As it is written in Isaiah the prophet. Behold I send my messenger before your face, who will prepare your way, the voice of one crying in the wilderness; Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.” (Mark 1:2) In John’s gospel, John the Baptist tells the priest and Levites who question him, “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness, ‘Make straight the way of the Lord, as the prophet Isaiah said.” (John 1:23)

One can imagine a certain kind of biblical critic having a discussion with Mark, or perhaps even with John the Baptist himself: “No, no, no. You’ve got it quite wrong. Whoever wrote Deutero-Isaiah certainly was not thinking about you, John. And you don’t even have the Hebrew right. It’s not ‘The voice of one crying in the wilderness.’ It’s “A voice cries,’ full stop. ‘In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord,’ full stop. The voice is not in the wilderness. The way is in the wilderness. The way is the way back from Babylon, to Jerusalem which goes through the wilderness. I’m sorry,” says the critic. “But in my upcoming course entitled Gunkel and Geschichte: A Form-Critical Introduction to Deutero and Trito-Isaiah in their Historical and Cultural Setting, John the Baptist gets a ‘C’!”

And, yet . . . isn’t there something of a nagging voice in the back of our minds that gets just a bit irritated with this kind of critic? “Yes, yes, yes. Of course. No doubt everything you’re telling us about the original context in which this passage from Isaiah 40 was written is correct. And yet . . . Handel was right! And Mark and the other gospel writers were right! And John the Baptist himself was right! John is the voice crying, ‘Prepare the way of the Lord.’ And the Lord for whose way he prepares is Jesus!”

If we are going to have a Christian reading of the Bible we have to be able to say both. The reason we have to say both is that, for Christians, the Bible consists of Two Testaments. And we have to take both Testaments seriously.

If we take the Old Testament seriously as Scripture, we have to take it seriously in its literal historical sense. Christians have sometimes been guilty of using the Old Testament as a kind of spring board to get to the New Testament—and the sooner we get there, and leave all that Old Testament stuff behind, the better.

But if we are going to take Isaiah seriously as Scripture, we have to take seriously Isaiah’s actual message. And we have to take seriously that the second half of Isaiah really is about Israel’s return from captivity in Babylon after the exile. The Cyrus that Isaiah talks about in Isaiah 45:1 really is the Cyrus who conquered Babylon and allowed the exiled Israelites to return from captivity five hundred years before Jesus or John the Baptist were born.

At the same time, if we are going to take the New Testament seriously, we have to take seriously that the New Testament interprets the Old Testament as being about Jesus. And one of the ways in which the New Testament interprets the Old Testament as being about Jesus is to engage in figurative readings. It is not just icon painters and allegorical interpreters of Scripture like Origen who engage in figurative interpretation of the Old Testament. The New Testament itself does it. And the way in which the gospels associate Isaiah 40 with John the Baptist is an example.

I confess that I myself have been the victim of graduate level theological education. It has taken me awhile to appreciate that there is something more going on in figurative interpretation than simply bad exegesis, trying to find a Christian meaning in an Old Testament text that just is not there. I confess that when I was younger I used to take a certain pride in disabusing simple Christians of their pious but mistaken readings of the Old Testament.

But rejoice! There is salvation even for theologians with Ph.D’s! I have finally seen the light! C. S. Lewis, in an essay entitled “Second Readings” in his book Reflections on the Psalms (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1958) looks at the question of figurative reading in a helpful way. I like Lewis’s term “Second Readings” better than “figurative interpretation” or “allegorical interpretation” because, rather, than suggesting that New Testament writers like Mark of Paul have misread, or deliberately distorted the Old Testament text, they have instead seen the way we cannot help but read an earlier Old Testament text as having said more than it meant originally, when we read it in the light of Jesus.

Lewis illustrates his point by referring first not to a biblical text, but to some pagan ones, including Plato’s description in the Republic, of a perfectly righteous man who is treated with contempt when he comes among ordinary people, who bind him, scourge him, and finally kill him by impaling him on a stake. There is a similar example in the Apocryphal book of Wisdom where the unrighteous decide to oppress the righteous poor man.

Let us lie in wait for the righteous man, because he is inconvenient to us and opposes our actions; he reproaches us for sins against the law and accuses us of sins against our training. He professes to have knowledge of God and calls himself a child of the Lord. . . . Let us see if his word are true, and let us test what will happen at the end of his life, for if the righteous man is God’s son, he will help him, and will deliver him from the hand of his adversaries. Let us test him with insult and torture . . . Let us condemn him to a shameful death for, according to what he says, he will be protected. (Wisdom 2: 10-20).

For a Christian, it is almost impossible to read these descriptions, and not think of Jesus, although they were written well before Jesus lived. Similarly, I would imagine there are few Christians, even those who have been trained strictly in the rules of modern critical exegesis, who can read the account of the Suffering Servant in Isaiah 53, and not think of Jesus.

Lewis suggests that in the real world these resemblances are not irrelevant. Hundreds of years before Jesus came along, Plato was able to imagine what would happen if someone like Jesus came along because that is how wickedness treats goodness when it is confronted by it. Look what happened to Martin Luther King, Jr. in our own time! But, how much more would it be the case that when God works through his chosen people the nation of Israel, and works through their prophets, and through them creates a literature in anticipation of his coming among us in person through the incarnation, that that there will be anticipations of God’s redemption in Christ that appear in that literature? How could it be otherwise?

So it is perfectly natural for the New Testament writers to engage in these second readings of Old Testament texts. They are a key to discerning the connection between the Old Testament and the New Testament because they are based on real connections. The readings may be figurative, but they are not arbitrary. If the God of who raised Jesus from the dead is the same God who delivered Israel from slavery in Egypt, and then delivered Israel again from exile in Babylon, it is not arbitrary to see a connection between the Exodus or the return from exile in Babylon, and the deliverance from sin and death that Jesus’ death and resurrection bring. If God wrote the script, he knows the plot-line!

What might be the second reading that we find in Isaiah 40? Well, first, before we find the second reading, we need to pay attention to the first reading. In just a few short points, what is that reading?

First, Israel’s exile is ended. Israel has been punished for her sins, and she is delivered from her captivity.

Second, Israel’s God is returning to Zion, to the same cities of Judah that had been taken into captivity.

Third, what is the wilderness? I would suggest that the wilderness is not the distance that Israel has to travel between Babylon and Jerusalem. Rather, as in the earlier Exodus from slavery in Egypt, the wilderness is the place of exile and judgment (following Christopher Seitz in The New Interpreter’s Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2001), vol. vi: 335). Israel is being delivered from the wilderness to come once again into the Promised Land.

There is a contrast between God’s divine sovereignty in delivering Israel and human weakness. All flesh is grass. The Babylonians, who had held Israel in captivity, who seemed so powerful, are actually grass. It is God who controls history, not the Babylonians.

Finally, it is God who brings victory, but he brings victory, not as a conqueror, like the Babylonians, but as a shepherd. God cares for Israel the way that a shepherd cares for his sheep.

How does the New Testament take up these themes from Isaiah in a second reading?

First, it is John the Baptist who is the voice pronouncing in a new situation that Israel’s exile is ended. (Luke 3:2-6).

As in Isaiah, there is a lamb. Jesus is the lamb, but he is the lamb who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29). He is also the shepherd who seeks out and cares for the sheep, and lays down his life for them (Luke 15:4-7; John 10:14-18.)

Jesus is also the Lord—the kurios—whose road is prepared for by the voice. The Lord has indeed returned to Zion! (Luke 19:28-40; Acts 2:36; 10:36; Phil. 2:1).

Finally, all flesh is grass! John the Baptist will preach that those who respond to the message with resistance will be separated like chaff from wheat (Luke 3:17).

Zechariah’s prophecy in this morning’s reading from Luke (2:68-79)—which has come to be known as The Benedictus—has many of the same themes.

God’s people are in exile, but God has visited and delivered his people. God’s promises through his prophets have been fulfilled, and God has remembered his covenant with Israel. God’s people have received the forgiveness of their sins. John the Baptist is the new Prophet of the Most High. He is the voice crying in the wilderness. And Jesus is the Lord whose way is prepared, who brings salvation and forgiveness of sins, and gives light to those in darkness.

This is how the New Testament writers have interpreted the Old Testament. But it is a second reading. The key issue that has to be addressed is that of continuity. How do we know that the connection that the New Testament writers draw between Isaiah’s “voice” and John the Baptist, between the Lord who returns to Zion, and Jesus, who is called “Lord” by Christians is a legitimate reading? Why is it not arbitrary?

The thing about second readings is that they are second readings. It is always possible to point to the literal meaning of the original text, and refuse to follow the interpreter who tries to point to a connection. It is always possible to claim that the so-called second reading is really nothing more than seeing pictures in clouds, pictures that exist only in our imagination.

However, I am going to suggest three connections that the New Testament writers draw in their second readings of Old Testament texts, connections with the life of Jesus that make the second readings almost inevitable, and especially connections with Isaiah.

First, there are Jesus’ words and deeds. In Luke 4, Jesus begins his ministry in Nazareth by citing Isaiah 61, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives.” (Luke 4:16-19; cf. Is. 61:1-2). Throughout Jesus’ ministry, his preaching and his miracles are signs that God’s kingdom is present, that Israel’s exile has ended. When John is imprisoned, he sends messengers to Jesus to question whether he really is “the one to come”? And Jesus replies by citing Isaiah: “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, and the dead are raised up!” (Luke 7:22-23; cf. Is. 29:18). Jesus is asking John to engage in a second reading.

Second, there are two themes in Isaiah 40-66 whose connection is never really explained. On the one hand is the theme of deliverance from exile and a new creation. On the other the story of the Suffering Servant. How do these fit together?

The consistent claim of the New Testament is that it is Jesus’ resurrection from the dead that ties them together. Jesus himself and the early church saw his crucifixion as a typological fulfillment of the suffering of the Servant (Luke 24:25; Acts 8:32-36). It is a second reading. In Jesus’ own words, his death is a “ransom for many” (Mark 10:45; cf. Is. 53:10).

At the same time, Jesus’ resurrection is the vindication of the Servant. It is also the clue to the Servant’s identity. The New Testament is clear that in raising Jesus from the dead, God proclaimed him not only as Christ, but as Lord (Rom. 1:4). The Suffering Servant is the dying and risen Lord whose way has been prepared by John.

Finally, the resurrection is the new creation by which Jesus creates a new people. The church is the people who have been brought back from exile. They are both Jews and Gentiles who come to Zion (Acts 1:8; Is. 60).

The key to the legitimacy of the second reading is the resurrection. If God really has raised Jesus from the dead, then it is almost impossible to avoid the second readings. If God has raised Jesus, then his crucifixion really makes sense as the Suffering Servant whose death is a ransom for sins. If God has raised Jesus, then Jesus’ claim that his preaching and miracles were deliverance to the captives, and sight to the blind as signs of a new return from exile just makes sense. If God has raised Jesus, then Jesus is the Lord who has returned to Zion, and John is the voice who calls on Israel to prepare for the coming of her Lord!

But we cannot stop there. The question of second readings is not just a question about continuity between Jesus and Israel, but of Jesus and the church. Where does this church fit in all of this? To see Jesus as the fulfillment of Isaiah’s vision of deliverance from exile demands that we see things through faith in Jesus’ resurrection. It is because God has raised Jesus from the dead that we can believe that God has delivered us from exile. We are the new people made up of both Jews and Gentiles. The church is the New Jerusalem, and Jesus is the Lord who has visited her.

At the same time, second reasons demand faith because the readings are not self-evident. From external appearances, exile continues. We believe that Jesus has brought salvation, but many continue to live in bondage. Jesus is the Lord who has visited his people, but he is also the Suffering Servant, and to follow Jesus means to share in his sufferings. Our sins are forgiven, but we still sin, and we still look forward to our final deliverance. Every mountain has not yet been brought low. Every valley has not yet been raised up. All flesh is still grass, and until Jesus returns, like the author of the second half of Isaiah, we must still wait in hope for there to be no more tears and no more death.

In the meanwhile, however, we can still rejoice with Handel in singing “Comfort, Comfort, my people,” because we know that our Redeemer lives. And we have confidence that some day “All flesh shall see it together!”

This was an incredible sermon as you preached it a week-and-a-half ago, Bill. Thank you for it.

Comment by Chip — July 4, 2010 @ 5:39 pm