1 Samuel 16:1-13

Ephesians 5:(1-7)8-14

John 9:1-13(14-27)28-38

Psalm 23

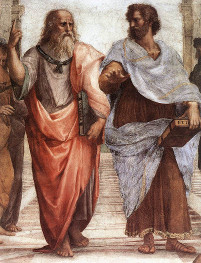

Recently, I have been reading a book about the influence of the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle in the history of Western civilization. It is a fascinating book that shows how these two Greek philosophers who lived approximately four hundred years before the birth of Jesus Christ have repeatedly influenced Western thought for over two milennia. The book is entitled The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization.1 The title takes its name from Plato’s famous analogy of the cave. You’re familiar with the analogy? In Plato’s dialogue, The Republic, Socrates suggests that the human situation is something like that of a group of people who have been chained in a cave all of their lives facing a blank wall. Behind the people are a group of figures whose shadows are being cast on the wall in front of them by a fire –something like shadow puppets –and the people are trying to make sense of the silhouettes. These shadows are the only reality the people know. Socrates then asks what would happen if someone were to be released from the cave and were to venture out into the world above to see the sun and nature as it really exists. If such a person were then to return to the cave and tell what he or she had seen, the man or woman would not be believed. The people in the cave know what reality is. It is the shadows that they can see on the wall. They cannot imagine anything else.

Recently, I have been reading a book about the influence of the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle in the history of Western civilization. It is a fascinating book that shows how these two Greek philosophers who lived approximately four hundred years before the birth of Jesus Christ have repeatedly influenced Western thought for over two milennia. The book is entitled The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization.1 The title takes its name from Plato’s famous analogy of the cave. You’re familiar with the analogy? In Plato’s dialogue, The Republic, Socrates suggests that the human situation is something like that of a group of people who have been chained in a cave all of their lives facing a blank wall. Behind the people are a group of figures whose shadows are being cast on the wall in front of them by a fire –something like shadow puppets –and the people are trying to make sense of the silhouettes. These shadows are the only reality the people know. Socrates then asks what would happen if someone were to be released from the cave and were to venture out into the world above to see the sun and nature as it really exists. If such a person were then to return to the cave and tell what he or she had seen, the man or woman would not be believed. The people in the cave know what reality is. It is the shadows that they can see on the wall. They cannot imagine anything else.

Arthur Herman, the author of the book, contrasts Plato’s understanding of reality – knowing the unchanging truth that lies behind the illusory shadows – with Aristotle’s. In contrast to Plato’s focus on knowing the permanent and unchangeable, Aristotle insisted that we could find reality in the ordinary day to day world in the midst of which we live our lives. Where Plato wanted to leave the cave, Aristotle insisted that the cave was where we needed to get to work.

Each philosophy has its consequences for how we live. To be simplistic, Plato’s philosophy included an ethic that focused on knowledge, specifically, knowledge of that which is certain and permanent and about which one cannot be mistaken. Aristotle’s ethic focused instead on what he called “practical knowledge,” that is, how to get things done in a world that was not certain or permanent, and which changed constantly. So Plato’s prescription for how we should live focuses on “knowing.” Aristotle’s focuses on “doing.” There’s a silly joke that’s been around for awhile that gets the philosophers wrong, but basically gets the idea right, so I’ll adjust it by providing the correct names. Plato said: “To be is to do.” Aristotle said: “To do is to be.” Frank Sinatra said: “Do be do be do.” And, of course, Fred Flintstone said: “Yabba Dabba Do.” And Scooby Do said “Scooby Dooby Do.”

Both philosophies have their influences, and also their characteristic errors. The characteristic error of Platonism would be the Socratic fallacy. If we only know the right thing, we’ll be sure to do it. Of course, that is not the case. We all do things that we know we should not do. The characteristic heresies associated with Aristotle are perhaps Pelagianism and antinomianism. Although these are opposite heresies, they are both characterized by a focus on action, on what we do rather than on what we know, on, as we say, “pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps.” So today the descendents of Plato would be the ideologues, the people who spend hours on their computers typing comments on social media because someone on the internet said something that was wrong. The descendents of Aristotle are the activists. They can be do-gooders who try to change the world for the better, but they can also be the busy bodies who make everyone else’s life miserable by trying to straighten them out.

Why bring up Plato and Aristotle in a Lenten sermon? As we look at the lectionary readings these morning, we note that there is a common theme about “seeing” and “light,” especially when we compare the gospel and epistle readings. John’s gospel tells the story of Jesus healing a man born blind. Before Jesus heals the man, he says: “As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world.” (John 9:6). At the end of the passage, Jesus says: “For judgment I came into this world, that those who do not see may see, and those who see may become blind.” (v. 39). The Ephesians passage contains the statement: “Walk as children of light . . . and try to discern what is pleasing to the Lord” and concludes, “But when anything is exposed to the light, it becomes visible. . .” (Eph. 5:8,14) The similarities to Plato and Aristotle are certainly intriguing. There is the same imagery of light and darkness. The John passage, like Plato’s analogy of the cave, focuses on “seeing.” To the contrary, while the Ephesians passage uses light imagery with its contrast between light and darkness, the focus is on “doing,” more like Aristotle. John seems to be focusing on knowing the light. Paul focuses on “walking in the light.”

At the same time there are clear differences between our New Testament texts and Plato and Aristotle. Both John and Paul engage in what I like to call “christological subversion.” Christological subversion is a process in which the New Testament writers take our ordinary ways of talking or thinking about things and turn them inside out and upside down. A classic example would be the notion of power. In the New Testament, the almighty power of God is demonstrated not in the destruction of God’s enemies but in what Paul calls the “foolishness of the cross” (1 Cor. 1:18), the cross on which the crucified Son of God bears the sins of the world, and prays for his enemies, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” (Luke 23:34)

Let’s look first at how this works in the gospel of John. For John, the focus is not, as in Plato, on the contrast between knowledge and ignorance, but on the contrast between faith and willful unbelief. Moreover, John reverses Plato’s elitist contrast between wise philosophers who see the light and ordinary slobs who happily live in the midst of ignorance and darkness. The equivalent of Plato’s wise philosopher in the gospel story are the religious leaders who ask Jesus rhetorically at the end of the passage: “Are we also blind?” (John 9:40) In asking the question, they assume that they can see. The man who is released from blindness is not a paragon of wisdom or philosophical clear-sightedness, but an ordinary beggar, a man who sits by the side of the road, and who is so low on the status totem pole that Jesus’ disciples don’t hesitate to use him as a moral object lesson when they ask Jesus, “Who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (v. 2) The man does nothing to earn or deserve having his sight restored, and does not even request healing (as is usually the case in healing stories in the gospels). Jesus simply heals him with the stated purpose that “the works of God might be displayed in him.” (v. 3)

Throughout the story, the contrast between light and darkness, between sin and “God’s glory” is played out. The religious leaders appeal to Moses, and to their own status as disciples of Moses, and suggest that, since Jesus had healed on the Sabbath, he must be a sinner. In light of Plato’s focus on the certainty of “knowledge,” it is interesting to compare the number of times that the word “know” occurs throughout the story. The religious leaders state: “We know that God has spoken to Moses, but as for this man, we do not know where he comes from.” (v. 29) The man’s parents state “We know that this is our son and that he was born blind. But how he now sees we do not know, nor do we know who opened his eyes.” (v. 21-21) The blind man himself knows only what has happened to him, and in his own way also appeals to Moses: “Whether he is a sinner I do not know. One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see” (v. 25) and a bit later, “We know that God does not listen to sinners, but if anyone is a worshiper of God and does his will, God listens to him. Never since the world began has I been herd that anyone opened the eyes of a man born blind. If this man were not from God, he could do nothing.” (v. 31-33)

Now let’s turn to Paul. In Ephesians 5, there is a contrast between light and darkness that is also reminiscent of Plato: “[A]t one time you were darkness, but now you are light in the Lord.” (v. 7) But, as I have already mentioned, the overall focus sounds more like Aristotle, on doing rather than knowing. Paul contrasts the behavior of those who walk in darkness with those who walk in light: “But sexual immorality and all impurity or covetousness must not even be named among you. . . . Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them.” (v. 3,11) And the focus is on action, on doing, as in Aristotle: “Walk as children of light . . .” (v. 9) In verses 15 following, not included in the lectionary reading, Paul goes on to write: “Look carefully then how you walk, not as unwise but as wise, making the best use of the time, because the days are evil.”

It certainly would be possible to read Ephesians 5 as a series of Aristotelian imperatives, Paul’s prescription for how to get things done. But, as in John, Paul engages in what I call “christological subversion.” He rather turns our ordinary way of looking at things upside down. The key to reading the passage is found in verse 1: “Therefore be imitators of God, as beloved children.” This is the only passage in the Bible where we are told to be imitators of God, but Aristotle would certainly never have suggested this. The Aristotelian God was the “unmoved mover,” who did nothing but think “self-thinking thought.” The Unmoved Mover did not not even know human beings existed, so he was not someone to imitate.

How then do John and Ephesians differ from Plato and Aristotle? What marks the difference between Christianity on the one hand and the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle on the other? First, and, most important, for both John and Paul, the light that is contrasted with darkness is identified not with an abstract philosophical principle, but with a historical person, a Jew from Nazareth named Jesus. For both John and the apostle Paul, the divine light who is the source of all truth and all goodness has become a human being by becoming flesh in Jesus Christ. The Logos of Plato has become incarnate in Jesus. Aristotle’s unmoved mover has moved among us. We do not have to leave the cave to seek the light. The light has come into the cave to find us.

Jesus claims at the beginning of the the gospel passage in John 9, “I am the light of the world” (v. 5), and the controversy about the identity of this light is the key theme throughout the chapter. There is a progress of both belief and unbelief throughout the story. The blind man first says that Jesus is a prophet (v. 17); later he compares him to Moses, and says that he is “from God” (v. 33) Finally, he acknowledges Jesus as the Son of man, and worships him as “Lord,” saying, “I believe” (v. 35-38). In contrast, the Pharisees first say that Jesus cannot be from God because he has healed on the sabbath (v. 16); they then state “We know that this man is a sinner.” (v. 24) Finally, they confront Jesus and ask him whether he is claiming that they are blind, to which Jesus replies: “If you were blind, you would have no guilt; but now that you say, ‘We see,’ your guilt remains.” (v. 40-41) The key issue in John’s gospel is not an epistemological issue as it is in Plato, “How can we be certain about what we know?,” but a moral issue, and it has to do with how we relate to the person of Jesus. For John, we know the light by committing ourselves to Jesus, who is himself the light. There is, accordingly, a moral dimension to faith. It is not just a matter of knowledge in the ordinary sense, but also of action. What we can know to be true is related to how we respond to Jesus who is the truth. To refuse Jesus is to refuse the light and to walk in darkness even if we think that we see.

The person of Jesus is also key for what it means to “walk in the light” in Paul’s letter to the Ephesians. Paul follows his statement about being imitators of God with a further statement about what this means: “Walk in love as Christ loved us, and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God.” (Eph. 5:2) Everything else that Paul says about “walking in the light” and “avoiding the works of darkness” in what follows depends on this initial statement. For Paul in Ephesians, we walk in the light because we walk in love. In the same way that Jesus loved us and gave himself for us on the cross, so we are to love one another. Paul concludes the passage, “Awake O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you.” (v. 14)

What then might be some of the implications we could draw from our reading of John and Ephesians? What does christological subversion say about knowing the light and walking in the light?

First, the contrast between a Platonic knowing the light and an Aristotelian walking in the light is a false contrast. It is clear that, for John, knowing the light has a moral dimension, and where we stand in relation to the light depends on where we stand with Jesus. This becomes especially clear in other passages in John’s gospel. Knowing and doing belong together: “If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” (John 8:31-32) In Ephesians, Paul makes clear that “walking in the light” is a “walking in love,” and this depends on knowledge, the knowledge that “Christ loved us and gave himself for us.” (Eph. 5:2) So, for John, to know the light we have to walk in the light, and the light is Jesus. And for Paul, to walk in the light, we have to know the light, and the light is Jesus.

The second thing that we can learn from John’s gospel and Paul’s letter to the Ephesians is that light is always prior to darkness. We do not create light. Rather, the light has already created us, and it came to us before we sought it. In John’s gospel, the blind man did not heal himself. Jesus healed him, and gave him sight. For Paul, we walk in love because Christ first loved us and gave himself for us. We did not die for Christ. He died for us. So it is not our job to free ourselves from the cave, and to seek the light. It is not our task to achieve the Aristotelian “golden mean” in order that we might become virtuous citizens so that that we might hope to attain the light. The light has come to us before we did anything at all, and has healed our blindness, even when we were still in darkness.

Third, for both John and Paul, a crucial new word is added to the mix, not just knowledge and action, but “love.” The light that has come to us in Jesus is a light that loved us even when we were unlovable. As Jesus sought out and healed a blind man who was so far beneath contempt that even Jesus’ disciples wondered whether he had sinned or his parents had sinned that he was in such a wretched condition, the light has sought us out when we were blind. Unlike the light of the philosophers, the light that comes to us in Jesus is not a light for elitist philosophers, but for everybody. This is a light that gives sight to blind beggars. The early Christian writer Origen said that Plato was like a chef in a five-star restaurant who only knew the recipes that appealed to gourmet customers. To the contrary, Jesus cooks for everybody.2

Finally, because the light has come to us in Jesus, we can now see clearly that there is a contrast between light and darkness. Having come to see the light, it makes no sense for us to walk in darkness any longer. Because we know the light, we are called to walk in the light. Of course, learning to walk in the light when we have been used to the darkness probably will not happen over night. It took awhile for the blind man who was healed by Jesus to figure out just who this man was who had given him sight. We should not be surprised if we stumble from time to time. But we no longer have to walk in darkness. To walk in the light is to abandon the path of darkness.

We might be tempted one last time to become good Platonists or Aristotelians and find ourselves saying, “Thanks for getting us out of the cave. We’ll take it from here.” But even here, both John and Paul undo the philosophers’ temptation to take things into our own hands. This is what the whole doctrine of grace is about, and that is a topic for another sermon. I’ll just mention in passing that both John and Paul switch to a different metaphor at this point, not light and darkness, but dwelling in Christ, and being indwelt by the Holy Spirit. In John’s gospel, there is the metaphor of vine and branches: “I am the vine; you are the branches. Whoever abides in me and I in him, bears much fruit. For apart from me, you can do nothing.” (John 15:5) For Paul, the metaphor is that of the body of Christ. Jesus is the head and we are the body: “Speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him, who is the head, into Christ . . . who makes the body grow so that it builds itself up in love.” (Eph. 4:15-16) Or we could just stick with the metaphor of light. As Paul writes in 1 Corinthians: “And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another.” (2 Cor.3:18) Once again, the main point is not that we create the light or seek it out, but that we can walk in the light because we have come to know the light that has shined on us when we were in darkness. As with Moses’s veil, part of what it means to speak about grace means that we have come to glow because we have been filled with the light of Christ. Imagine that the light with which Jesus shone on the Mount of Transfiguration is now contagious. But as I said, that would be a topic for another sermon.

I leave you with a prayer of St. Richard of Chichester who sets out the path before us, a prayer that we might know the light and walk in the light.

Thanks be to Thee, my Lord Jesus Christ

For all the benefits Thou hast given me,

For all the pains and insults Thou hast borne for me.

O most merciful Redeemer, friend and brother,

May I know Thee more clearly,

Love Thee more dearly,

Follow Thee more nearly.

Amen

1 Arthur Herman, The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization (New York: Random House, 2013).

2From Herman, p. 161.

I have greatly enjoyed this post. I like the way you have teased out the various principles from the two biblical texts; it takes skill to do this kind of exposition, drawing as you did, relevant resources from Plato and Aristotle.

Comment by K Tham LIM — April 20, 2014 @ 1:15 pm