Broadly speaking, the 39 Articles stands within the tradition of Anglicanism as “reformed catholicism,” or, more specifically, a reforming movement within the western catholic church. (This contrasts with more radical Reformation movements, such as the Anabaptists, and, arguably, the Puritans,who viewed themselves as completely breaking with western catholicism to return to the pristine Christianity of the New Testament.)

Broadly speaking, the 39 Articles stands within the tradition of Anglicanism as “reformed catholicism,” or, more specifically, a reforming movement within the western catholic church. (This contrasts with more radical Reformation movements, such as the Anabaptists, and, arguably, the Puritans,who viewed themselves as completely breaking with western catholicism to return to the pristine Christianity of the New Testament.)

The Articles are largely an ecumenical document, the majority of whose statements fall broadly within the parameters of “reformed catholicism.”

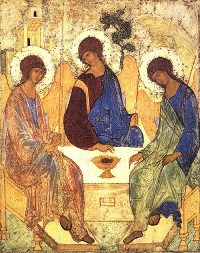

Arts. 1-5, 8 affirm historic creedal Nicene and Chalcedonian Christianity.

Arts. 9-10,12-13,15-18 affirm the positions of a moderate Augustinianism. Even art. 17 does not teach a specifically Calvinist doctrine of predestination. There is nothing about negative predestination (reprobation or double predestination). The election that is described is corporate and “in Christ.” (“In Christ” was added to the original 42 Articles.) “Arminians” such as Richard Hooker were able to affirm this article, to the chagrin of strict Calvinists.1

Arts. 6, 7, 11 affirm the sufficiency and primacy of Scripture as well as justification by faith, which are commonly held Reformation positions, although even here, an argument could be made that the position on Scripture is consistent with that of the patristic church, of Eastern theologians such as John Damascene, and Western theologians such as Thomas Aquinas. Anglican theologians such as Cranmer, Jewel, and Hooker make clear that (contrary to the Puritan hermeneutic), Anglicans do not understand the “Scripture principle” in a “regulative” sense.

The “controversial” articles are those articles, especially beginning with Art. 19, “Of the Church,” in which the position of the Church of England is set over against that of other contemporary Reformation-era churches, usually the Tridentine Roman Catholic position, but sometimes that of other Reformation churches, usually those of the Radical Reformation. (Arts. 38-39 are addressed against Anabaptists).

Which of the articles have been “controversial” in the history of Anglicanism and today? Art. 22, repudiating purgatory and icons; Art. 25, concerning the number of sacraments, and seemingly forbidding elevation of the consecrated host; Art. 28-29, which seem to reject any notion of bodily presence (not simply transubstantiation, but also the Orthodox or Lutheran positions) and elevation of the host; Art. 31, which appears to reject any notion of eucharistic sacrifice. Generally, Evangelical Anglicans have tended to be happy with these articles, and Anglo-Catholics unhappy. Conversely, Art. 27 seems on a literal reading to affirm baptismal regeneration, a position not embraced by a good many Evangelical Anglicans.2