I received an email recently that asked for clarification in light of a concern that regularly appears in complementarian criticisms of egalitarian theology — that egalitarianism presumes that there simply are no differences whatsoever between men and women. Behind this also lurks another unspoken (but sometimes spoken) criticism — that egalitarian theology inevitably leads to various kinds of sexual anarchy and licentiousness. (I don’t suggest that the writer harbors this assumption.)

I received an email recently that asked for clarification in light of a concern that regularly appears in complementarian criticisms of egalitarian theology — that egalitarianism presumes that there simply are no differences whatsoever between men and women. Behind this also lurks another unspoken (but sometimes spoken) criticism — that egalitarian theology inevitably leads to various kinds of sexual anarchy and licentiousness. (I don’t suggest that the writer harbors this assumption.)

The email’s title was:

“Looking for ontological exploration of men and woman from an egalitarian worldview”

“Most of the books I have read state that Egalitarians do not believe that men and women are exactly the same, but I haven’t found a book yet that offers any theories or descriptions of the categories of men and women from a mutualist/egalitarian perspective. I haven’t yet found an egalitarian that explores the difference (traits, purposes within those traits distinct between the two) in light of equality.”

“I was wondering if you had any writing on the subject or any guidance on where I might find such an exploration.”

Mxxxxx,

I have not been able to spend much time on these issues for the last year or so as I have been working on other things. I need to get back to addressing some of these questions.

Since your subject title concerns ontology, I would refer you to chapter 14 and the conclusion of Icons of Christ (Baylor University Press, 2020) where I lean on Roman Catholic philosopher Norris Clarke’s trinitarian ontology, Karl Barth’s relational understanding of sexuality, and on Dorothy L. Sayers’s essay “Are Women Human?”

Crucial to Clarke’s position is (as he titles an essay) “To Be Is To Be Substance-in-Relation,” in Explorations in Metaphysics (University of Notre Dame Press, 1994). Also see his Person and Being (Marquette University Press, 1998), which I cite in ch. 14.

According to Clarke, every being has both an itself dimension (substance) and a toward other dimension (relation). For human beings, substance is tied both to rationality and embodiment – Aristotle: “the human being is a rational animal” – and it is this element of rationality on which Boethius focused in his definition of personhood – “an individual substance of a rational nature.” However, one of the great contributions of patristic christology and trinitarian theology is that it is crucial to distinguish person and nature – something lacking in Boethius’s definition.

Drawing on Trinitarian theology, all persons have a rational nature (Boethius) but to be a person simply is to be in relational orientation to other persons. In the Trinity, the Father simply is the one who generates the Son and who with the Son brings forth the Spirit through procession. The Son simply is the person who is generated by the Father and who with the Father gives being to the Spirit, and the Spirit simply is the person who proceeds from the Father and the Son.

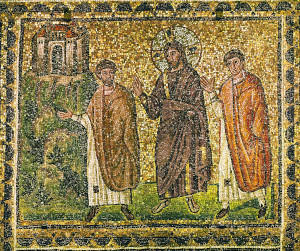

Applied to humanity, in the realm of substance or essence, there can be no ontological difference whatsoever between men and women as it is the common essence of rational embodiment that makes human beings human. If there were any ontological difference of essence/nature/substance as far as humanity, men and women would each be a distinct species, and the Word would have to have become incarnate twice (once as a male and once as a female) in order to redeem humanity. The orthodox doctrine of the Incarnation is not that the Word assumed a male human nature but that the Word assumed a human nature common to men and women; however the manner in which the incarnate Word exists as human is as the male Jesus of Nazareth.

As with the Trinity, I would suggest that the fundamental ontological distinction between men and women exists at the level of relation, not substance (or essence). To be a human being means to share in the common rational equality that is essential to human nature, but to be a male human being is to exist as relationally oriented to the female, and to be a female human being is to exist as relationally oriented toward the male. To be a human being means to exist either as a male or as a female and to exist in equal partnership in relation to the other.